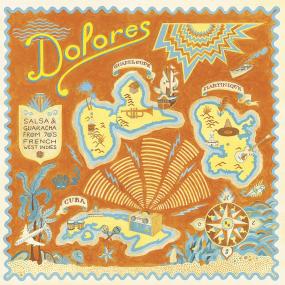

DOLORES - SALSA & GUARACHA FROM 70'S FRENCH WEST INDIES by VARIOUS ARTISTS

| SKU | 141351 |

| Artist | VARIOUS ARTISTS |

| Title | DOLORES - SALSA & GUARACHA FROM 70'S FRENCH WEST INDIES |

| Label | BORN BAD RECORDS |

| Catalog # | BB 183LP |

| Tag | |

| Release | W 37 - 2025 |

| Format | Vinyl - EU2LP |

| EAN Barcode | 3516628490514 |

| Benelux exclusive, Import | |

| € 28,50 | incl. VAT, excl. shipping |

Tracks

- mavaloi - te traigo guajira

- los caraibes - donde

- tropicana - amor en chachacha

- ryco jazz - wachi wara

- eugene balthazar - dap pignan

- roger jaffory - oey mi consejo

- les kings - oriza

- la perfecta - tumbadora

- les supers jaguars - tatalibaba

- super combo de pointe-noire - serrana

- lensemble abricot - se quedo boogaloo

- henri guedon - bilongo

- les aiglons - pensando en ti

- los martiniquenos - caterete

Description

14 tracks unfold a rarely heard blend of salsa, guaracha and Afro-Caribbean sounds from the 1970s French West Indies. This collection draws from both urban and rural roots across the Creole archipelago, connecting to what Edouard Glissant described as "the trace of singing erased by slavery." Malavoi, a celebrated Fayolais orchestra, opens with a 1974 take on Ray Barretto's guajira; while the compilation closes with Los MartiniqueNos de Francisco performing danmye-influenced Caterete, an Afro-Colombian champeta originally penned by Fabian Ramon Veloz Fernandez. Studded in between, Los Caraibes reimagine Cuban classic Donde with Martinique vocalist Joby Valente, while Haitian-influenced Tropicana keep the dancefloor moving with Amor En Chachacha, and Congolese Ryco Jazz and Guadeloupe's Super Combo add their Latin jazz and salsa spins.

Comes with download code and 6 page booklet with liner notes in French, Spanish & English

==================================

In Guadeloupe, many people think that jazz and ka music are like a ring and a finger. To some extent, the same could be said about so called Latin music and the music played in the French West Indies. Both aesthetics were born in the Caribbean and bear so many connections that they can easily be considered cousins. In constant dialogue, there are lots of examples of their fruitful alliance and have been for a while. The English country dance that used to be practiced in European lounges came to be called kadrille in Martinique and contradanza in Cuba. They both featured additional percussion instruments inherited from the transatlantic deportation. Drawing from shared feelings about the same traumatized identity – later to be creolized – it would be hard not to assume that they were meant to inspire each other.

The golden age of the orchestras that graced the Pigalle nights during the interwar period further proves the point. As soon as the 1930s, Havana-born Don Barreto naturally mixed danzón and biguine music in a combo based at Melody's Bar. In the following decade, Félix Valvert, a conductor who was born and raised in Basse-Terre in Guadelupe, also worked wonders in Montparnasse with La Coupole, which was an orchestra made up of eclectic musicians. Afro- Caribbean performers of various origins were often hired on rhythm and brass sections in jazz bands, which used to enliven the typical French balls of the capital. In the 1930s and onwards, Rico’s Creole Band was one of them. Martinican violinist-clarinettist Ernest Léardée, who would become the king of biguine music as well as the main figure of French Uncle Ben's TV commercials (a dark stigma of post-colonial stereotypes), had musicians from the whole Caribbean sphere play at his Bal Blomet – and they all enchanted "ces Zazous-là" (according the words of Léardée's biguine-calypso piece).

In les Antilles (French for French West Indies), music history started to speed up in the 1950s, when trade expanded and radio stations grew bigger. The Guadelupean and Martiniquais youth tuned in their old galena radio sets to South American and Caribbean music. As for the women traders, les pacotilleuses, they bought and sold goods across different islands (the "passing of items through various hands" was thought to be most pleasurable) and brought back countless sounds in their luggage. Such was the case of Madame Balthazar, who once returned from Puerto Rico with the first 45rpm and 33rpm to ever enter Martinique. Out of this adventure was created the famous Martinican label La Maison des Merengues, a music business she opened and undertook with her husband and which proved to be a major landmark.

At the end of the 1950s, in Puerto Rico, Marius Cultier competed in the Piano International Contest playing a version of Monk's Round 'Midnight. He won the first prize and this distinction foreshadowed everything that was to come. Cultier, the heretic Monk of jazz, was quickly praised for writing superb melodies, always tinged with a twist that conferred a unique sound to his music. It didn't take long for the gifted self-taught musician to get to play with Los Cubanos, making a name for himself thanks to his impressive maestria on merengues. The rest is history. Besides, in the late 1950s, Frantz Charles-Denis, born into the upper middle class in Saint-Pierre and better known by his first name Francisco, went back home after working at La Cabane Cubaine – a club located rue Fontaine where he had caught the Latin fever. Francisco's music was therefore heavily marked by his Cuban cousins' influence, which gave the combos he led a

specific style and also led to renewal. Things were swinging hard in La Savane, located in the main square in Fort-de-France. He set up the Shango club close by and tested out the biguine lélé there, a new music formula spiced up with Latin rhythms. Soon afterwards, fate had him fly to Puerto Rico and Venezuela. As for percussionist Henri Guédon (percussions were only a part of his many talents), he was born in Fort-de-France in May 22nd 1944, the day marking the celebration of the abolition of slavery. As an old man, he could remember that in " [his] father's Teppaz, a lot of hectic 6/8 music was constantly playing...". In the opening lines of his Lettre à Dizzy, a small illustrated collection of writings published by Del Arco, he highlighted the huge impact that cubop had on him as a teenage boy, around 1960. He eventually turned out to be the lider maximo in La Contesta, a big band steeped in Latin jazz. He was also the one who originated the word zouk to describe music which brought the sound of the New York barrio to Paris. It was the culmination of a journey that started in Sainte-Marie: "a mythical place for bélé, the equivalent of Cuban guaguancó".

In the early 1960s, the tertiary economy developed to the detriment of agriculture. Yet rural life was where roots music emerged in Martinique and in Guadeloupe. Record companies played a major part in the process of Latin versions sweeping across the islands – before reaching everywhere else. Producer Célini, boss of the great Aux Ondes label, and Marcel Mavounzy, both the head of Émeraude records - a firm which was founded in 1953 - as well as the brother of famous saxophonist Robert Mavounzy, were big names to bear in mind. Although there were many of them - all of whom are featured on this record - Henri Debs was definitely the major figure in the recording adventure. He proved to be so influential that he even got compared to Berry Gordy. In the mid 1950s, when he acquired his first Teppaz, he worked on his first compositions: a bolero and a chachacha. Then, he became the one man who made people discover Caribbean music, from calypso to merengue. He was among the first ones to rush out to San Juan, Puerto Rico, to buy records and distribute them through a store run by one of his brothers in Fort-de-France. He had members of the Fania All Star come and perform there, which he was madly proud about. He was also the first one to pay attention to Haitian music, such as compas direct and various other rhythms which would soon flood the market. As a result, many of the combos hitting his legendary studio would end up boosted by widespread "Afro-Latin" rhythms. However, he never denied his identity: gwo ka drums were given a major role, although they were instruments which had long been banned from the "official" music spheres.

The present selection bears witness to such a creative swarming. Here are fourteen tracks of untimely yet unprecedented cross-fertilization: all types of music rooted in the Creole archipelago have found their way, whatsoever, to the tracklisting. Whether originating from the city or being more rural, they all go back to what Edouard Glissant, in an interview about the place of West Indian music in the Afro-American scope, called "the trace of singing, the one which got erased by slavery." "It is so in jazz, but also in reggae, calypso, biguine, salsa... This trace also manifests through the drums, whether Guadelupean, Dominican, Jamaican or Cuban... None of them being quite the same. They all point to the idea of a trace, seeking it out

and connecting to each other through it. This is the hallmark of the African diaspora: its ability to create something new, in relation to itself, out of a trace. It may be the memory of a rhythm, the crafting of a drum, a means of expression which doesn't resort to an old language but to the modalities of it."

The opening track features one of the emblematic orchestras of this aesthetic identity, criscrossing many music types from the archipelago. The 1974 Ray Barretto guajira – Ray Barretto was a major New York drummer influenced by Charlie Parker and Chano Pozzo – is magnificently performed by Malavoi, a legendary Fayolais group (i.e from Fort-de-France). Additionally, the compilation ends on a piece by Los Martiniqueños de Francisco. It symbolically closes the circle as it is a genuine potomitan of Martinique culture which also functions as a tireless campaigner for Afro-Caribbean music. Practicing the danmyé rounds (a kind of capoeiria) to the rhythm of the bèlè drum, it delivers a terrific Caterete, a kind of champeta of Afro- Colombian obedience which was originally composed by Colombian Fabián Ramón Veloz Fernández for the group Wgenda Kenya. The icing on the cake is Brazilian Marku Ribas, who found refuge in Martinique in the early 1970s, bringing his singing to the last trance-inducing track.

These two "versions" convey the whole tone of a selection composed of rarities and classics of the tropicalized genre, swarming with tonic accents and convoluted rhythms. It is the sort of cocktail that the West Indians never failed to spice up with their own ingredients. For instance, the Los Caraïbes cover of Dónde, a famous Cuban theme composed by producer Ernesto Duarte Brito, has a typical violin and features renowned Martinique singer Joby Valente and his piquant voice. The track used to be – or so we think – their only existing 45rpm. The meaningful Amor en chachachá by L'Ensemble Tropicana, a band which included Haitian musicians among whom was composer and leader Michel Desgrotte, also recalls how Latin music was pervasive in the tropics in the mid-1960s. They were the ones keeping people dancing at Le Cocoteraie in Guadelupe and La Bananeraie in Martinique. Around the same time, another "foreign" band, Congolese Freddy Mars N'Kounkou's Ryco Jazz, achieved some success on both islands by covering Latin jazz classics – such as their adaptation of Wachi Wara, a "soul sauce" by Dizzy Gillespie and Chano Pozo whose interweaving of strings and percussions can have anyone hit the dancefloor. How can you resist Dap Pinian indeed, a powerful guaguancó by Eugene Balthazar, performed by the Tropicana Orchestra and published by the Martinique-founded La Maison des Merengues? It also acts as a symbol of the maelstrom at work.

Going by the name Paco et L'orchestre Cachunga, Roger Jaffory used to play guaguancó too: his Fania-inspired Oye mi consejo is one example of his style. Baila!!!!! Dancing was also one of the Kings' focus points. Oriza is a Puerto Rican bomba and a "classic" originally composed by Nuevayorquino trumpeter Ernie Agosto, which reserves major space for brasses, giving it a special sheen. Emerging from the New York barrios crucible was also La Perfecta, a Martinique group originating from Trinidad, whose name directly references the totemic Eddie Palmieri

figure as well as his own band, also called La Perfecta. Here they borrow Toumbadora from Colombian producer and composer Efraín Lancheros and interpret it by emphasizing percussions, which set fire to the track even more than the wind instruments. The same goes for Martinique's Super Jaguars, who use Tatalibaba – a composition by Cuban guitarist Florencio "Picolo" Santana which was made famous by Celia Cruz & La Sonora Matencera – as a pretext for sending their cadences into a frenzy. In a more typically salsa vein, the Super Combo, a famous Guadelupean orchestra from Pointe-Noire that was formed around the Desplan family and had Roger Plonquitte and Elie Bianay on board, adapt Serana, a theme by Roberto Angleró Pepín, a Puerto Rican composer, singer and musician also known for his song Soy Boricua. Here again, their vision comes close to surpassing the original.

In the 1970s, L'Ensemble Abricot provided a handful of tracks of different syles, hence reaching the pinnacle of the art of achieving variety and giving pleasure. They played boleros, biguines, compas direct, guaguancó and even a good old boogaloo - the type they wanted to keep close to their hearts for ever, "pour toujours", as they sang along together in one of their songs. Léon Bertide's Martinican ensemble excelled at the boogaloo which had been composed by Puerto Rican saxophonist Hector Santos for the legendary El Gran Combo. Three years later, in 1972, Henri Guédon, with the help of Paul Rosine on the vibraphone, tackled the Bilongo made famous by Eddie Palmieri. Such a classic!!!!! And so were the Aiglons, the band from Guadelupe: choosing to execute Pensando en tí, a composition by Dominican Aniceto Batista, on a cooler tempo than the original, they noticeably used a wonderfully (un)tuned keyboard in place of the accordion. On the high-value collectible single – the first one released by Les Aiglons under the Duli Disc label – there is a sticker classifying the track under the generic name "Afro". Now that is what we call a symbol.